Most CFOs are genuinely comfortable with the way consulting spend is handled. There is governance in place, a process to follow, approvals to grant, and budgets that are rarely exceeded in spectacular fashion. From a distance, the category looks calm, contained, and—crucially—someone else’s operational problem.

That comfort usually lasts until the real numbers surface. Not the curated view that sits neatly in financial reports, but the consolidated reality of what the organization actually spends on consulting once the category is stripped of its disguises. The moment when “IT services,” “change support,” “transformation initiatives,” and a handful of creative accounting labels quietly collapse into one uncomfortable total is often the moment when confidence gives way to curiosity.

Part of the problem is semantic. Consulting is one of the few spend categories with no universally shared definition. Almost everyone is a consultant these days, from wedding planners to cybersecurity specialists to former strategy partners offering executive advice over coffee. When everything qualifies as consulting, anything resembling precise control becomes optional, and visibility becomes largely theoretical.

So when finance leaders say consulting spend is “under control,” what they usually mean is not that its value is clearly understood or actively optimized. What they mean is that a governance framework exists, invoices are validated, and nothing has gone catastrophically wrong. The process works, in the narrow sense that it does not fail loudly.

Return on investment, however, is a less comfortable topic. Asking whether the organization is consistently getting the best possible outcome from its consulting spend feels oddly confrontational, as if one were questioning the judgment behind long-standing relationships or reopening decisions that were already approved and paid for.

Yet as financial pressure increases and scrutiny intensifies, CFOs are increasingly expected to move beyond procedural reassurance. Consulting spend is no longer just a matter of control, but of impact, accountability, and strategic intent. And that shift begins by looking directly at a category many finance leaders believe they already understand—until they actually do.

The CFO’s Consulting Paradox

When CFOs think about consulting, they usually picture the visible part of the iceberg: strategic consulting projects, often run with top-tier firms. These engagements are executive-sponsored, well-framed, politically visible, and relatively easy to monitor. Fees are high, but scopes are clear. Decisions are documented. Outcomes are debated, even if not always measured.

From a finance perspective, this slice of consulting spend feels familiar and, importantly, manageable. It looks like an investment. It behaves like one. It receives attention because it sits close to the CEO and the board.

The problem is that it represents a surprisingly small fraction of total spend. In many organizations, strategic consulting barely accounts for ten percent of the overall consulting budget. Sometimes less.

The remaining ninety percent tells a very different story.

The Real Spend Is Elsewhere — And Mostly Unseen

The bulk of consulting spend lives in operational reality, not in boardroom decks. IT consulting, systems integration, operational excellence programs, process redesign, regulatory support, transformation PMOs, data projects, cybersecurity support—the list is long, unglamorous, and financially significant.

This is where consulting becomes diffuse. Engagements are smaller, more frequent, less standardized, and often renewed by habit rather than decision. They are initiated by operational teams, approved quickly, and rarely challenged on value creation. Individually, they look harmless. Collectively, they represent a structural drain on both budget and attention.

The point is not that it’s unmanaged; it’s that most of it doesn’t even show up as ‘consulting’ in a way finance can steer. And what cannot be clearly seen is rarely questioned.

The ROI Exception CFOs Never Intended to Create

Here lies the real paradox. CFOs are famously demanding when it comes to return on investment. Capital expenditures are scrutinized, business cases are dissected, synergies are challenged, and assumptions are stress-tested. Even relatively modest internal investments can trigger intense debate.

Consulting, however, often escapes this level of discipline.

Not because CFOs believe consulting is unimportant, but because it is framed as support rather than investment. Once a consulting project is approved, its value is implicitly assumed. The existence of governance is mistaken for evidence of impact. Completion becomes a proxy for success.

This creates a quiet exception to financial rigor. A category that absorbs millions, influences strategic and operational decisions, and shapes execution is rarely subjected to systematic ROI assessment. Asking whether value was truly delivered feels awkward, sometimes even inappropriate, especially when projects were sponsored by senior leaders and delivered by reputable firms.

Yet if the same logic were applied elsewhere—approving investments without tracking outcomes—it would be considered unacceptable.

Governance Without Curiosity Is Not Control

Most organizations can demonstrate that consulting procurement is governed. There are approval workflows, preferred suppliers, legal checks, and budget controls. From a compliance standpoint, the system works.

From a value standpoint, it is largely passive.

Governance answers the question “Was this allowed?” far more often than “Was this worth it?” Over time, that distinction matters. Consulting spend is neither chaotic nor optimized; it simply flows.

Because the most visible projects appear controlled, finance extrapolates order to the entire category—while most of the spend continues to operate below meaningful ROI logic.

The Risks No One Is Managing (Because No One Is Looking)

Consulting is usually framed as a cost issue. Occasionally as a performance issue. Rarely as a risk issue. That alone should make finance leaders uneasy.

In most organizations, consulting firms operate with a level of access and autonomy that would raise eyebrows in almost any other supplier category. They see sensitive data, influence strategic decisions, interact with senior leadership, and sometimes shape narratives that outlive the project itself. Yet the way risk is managed across consulting engagements is often superficial, inconsistent, or simply assumed away.

Not because CFOs are careless, but because consulting has benefited from a long-standing perception of trustworthiness. Reputable brand, reassuring partner, polished decks. Risk feels abstract, theoretical, and comfortably outsourced to legal clauses no one rereads after signature.

That comfort is misplaced.

Confidentiality Is Treated as a Checkbox, Not an Exposure

Most consulting projects involve access to confidential information: financial data, strategic roadmaps, M&A hypotheses, internal performance issues, organizational weaknesses. NDAs are signed, of course. That is where risk management usually stops.

What is rarely examined is how consistently confidentiality is enforced across engagements, especially when multiple consulting firms operate simultaneously across the organization. Data is shared through emails, shared drives, workshops, and informal conversations. Very few organizations maintain a structured view of who has access to what, for how long, and under which conditions.

From a finance and compliance standpoint, this is not a minor oversight. It is a structural exposure. When confidentiality is managed per project rather than per supplier and per portfolio, leakage becomes a matter of probability, not intent.

Conflicts of Interest Are Everyone’s Problem—So No One Owns Them

Consulting firms work with multiple clients, often within the same industry, sometimes on remarkably similar topics. This is not a secret, nor is it inherently unethical. What is problematic is the absence of a centralized mechanism to identify, document, and assess potential conflicts of interest across the consulting landscape of an organization.

Most conflict checks happen locally, at project level, based on declarations and good faith. They rarely account for what the same firm is doing elsewhere in the organization, or for how advisory roles overlap over time. Finance leaders typically assume that “someone” is managing this risk. Procurement assumes legal has it covered. Legal assumes business sponsors know what they are doing. Business sponsors assume the firm would say something if there were an issue.

For CFOs who demand strict controls on financial conflicts in audits, treasury, or M&A, the tolerance shown toward consulting conflicts is striking. Influence risk is treated as softer, less measurable, and therefore less urgent. Until it isn’t.

Decision Traceability Is Surprisingly Fragile

Consulting projects rarely fail loudly. What they do instead is dissolve quietly into organizational memory. Recommendations are delivered, slides are archived, and decisions are taken—or not—without a clear audit trail linking advice to outcomes.

From a compliance perspective, this is problematic. When regulators, auditors, or internal governance bodies ask why certain decisions were made, organizations can usually point to approvals and budgets. What they struggle to demonstrate is the logic behind choices, the alternatives considered, and the rationale for selecting a given consulting partner or approach.

In a world where decision traceability is increasingly expected, consulting remains oddly undocumented. Not because information does not exist, but because it is scattered across emails, presentations, and personal drives. The story can be reconstructed, but only with effort—and often with selective memory.

Finance leaders would never accept this level of opacity for capital investments. Yet for consulting, it is routine.

Risk Is Ignored Because Nothing Has Gone Wrong—Yet

The most dangerous aspect of consulting risk is that it rarely manifests immediately. Confidentiality breaches are subtle. Conflicts of interest are hard to prove. Poor advice does not trigger alarms; it simply leads to underwhelming outcomes that can be blamed on execution, culture, or market conditions.

This creates a false sense of security. As long as there is no scandal, no legal action, and no public failure, the category appears safe. But absence of incidents is often evidence of insufficient visibility, more than of lack of control.

Finance leaders are trained to think probabilistically, yet consulting risk is treated as binary: either something goes wrong, or it doesn’t. That mindset would be unacceptable in cybersecurity, compliance, or financial reporting. Consulting should not be the exception.

The uncomfortable truth is that consulting procurement often operates in a governance gray zone. Heavy on process, light on risk intelligence. Trusted by default, rarely verified in practice. And as long as consulting remains fragmented, poorly visible, and weakly documented, that gray zone will persist.

And the damage isn’t limited to value. Consulting gets access, influence, and information with far less scrutiny than any other supplier type—and finance usually notices only when it becomes a problem.

Finance Controls Consulting Like an Expense—And That’s the Core Mistake

Once you accept that consulting is the one category where ROI discipline goes missing, the next question becomes brutal and practical: what do you measure, and what do you stop funding?

Consulting is governed like an operating expense. Budgets are allocated annually. Spend is monitored against envelopes. Deviations are explained. Approvals are granted. From a financial control standpoint, the category behaves acceptably. Predictably, even.

The problem is that consulting is not an operating expense in the economic sense. It is an investment in judgment, capability, and acceleration. Treating it like office rent or travel costs does not reduce risk; it neutralizes ambition. The organization becomes very good at authorizing consulting and very bad at extracting value from it.

Finance ends up policing spend rather than shaping outcomes.

Why “Staying Within Budget” Is a Weak Success Metric

Most consulting projects are “in budget” before they even begin. The sourcing exercise produces proposals, one is selected, a number is agreed, and that number becomes the budget. Compliance is immediate. By definition.

Once the contract is signed, the financial discussion is effectively over. The project is not monitored against an economic hypothesis; it simply executes against a figure that was derived from the consultants’ own proposal.

What almost no one revisits is whether that budget was ever the right one in the first place.

Was the scope justified? Was the problem real, urgent, and worth externalizing now? Was consulting the best lever, or simply the fastest one? These questions belong upstream of procurement, yet they are rarely asked with financial seriousness. Once a project has executive sponsorship and a plausible narrative, the budget becomes a formality rather than a decision.

Compare this with any other investment category. Capital expenditures are debated before approval, challenged during execution, and reviewed after the fact. Consulting escapes this scrutiny not because it performs better, but because its value is harder to confront without creating friction.

So the real failure is not that consulting projects exceed budgets. It’s that no one cares whether the budget ever deserved to exist.

And in finance, that should be a deeply uncomfortable thought.

ROI Is Not the Same as a Business Case

Let’s be honest: most consulting projects do not come with a business case. They come with a justification.

A few slides, a burning platform, a timeline that magically cannot move, and a familiar sentence: “We need support.” Someone senior nods, procurement runs a sourcing process, finance validates the spend, and the organization has successfully converted “we think this is important” into “we are paying for it.”

When the ticket is a few hundred thousand, this is already questionable. When it becomes a few million, it turns into a habit that finance would never tolerate anywhere else.

The uncomfortable truth is that many consulting projects are approved without any explicit definition of outcomes. Not because outcomes are impossible to define, but because defining them forces a conversation people prefer to skip: Do we really need this? Now? At this price? And what will be different when it’s done?

Yes, some of consulting’s value is intangible. Culture shifts, leadership alignment, employee engagement, “momentum.” Fine. But “intangible” does not mean “unmeasurable.” It means you need to choose proxies, commit to them, and track them with the same seriousness you apply to any other strategic bet.

The category is also not one big blob. Most consulting projects fall into a few predictable families, and each family has a different ROI logic:

- Strategic projects: ROI is about decisions, prioritization, avoided mistakes, time-to-direction.

- Regulatory / compliance projects: ROI is about risk avoided, readiness, audit outcomes, and cost of non-compliance.

- Excellence projects (across functions): ROI is about measurable performance deltas—cycle time, cost-to-serve, productivity, error rates, working capital.

- Facilitateurs (IT, data, transformation PMOs): ROI is about execution acceleration, delivery reliability, adoption, and reduced rework.

None of this requires pretending consulting is a perfectly quantifiable asset. It requires refusing the lazy alternative: approving millions with no shared definition of success, and then acting surprised when “impact” becomes a matter of opinion.

That is the real paradox: CFOs demand outcome logic for almost every investment category—except the one that literally sells itself as “impact.”

The Portfolio Blind Spot

The deeper issue is that consulting is almost never managed as a portfolio. Projects are evaluated individually, approved individually, and forgotten individually. There is no aggregated view of how consulting investments compare, compete, or complement each other.

As a result, finance leaders cannot answer simple strategic questions with confidence:

- Which consulting initiatives delivered the most value last year?

- Which types of projects systematically underperform?

- Which firms generate repeat impact, and which generate repeat invoices?

- Where is the organization overspending relative to outcomes?

Without portfolio logic, prioritization is driven by sponsorship rather than economics. Urgency replaces value. Visibility replaces impact. The loudest project wins, not the most promising one.

Value Creation Requires Finance to Change Posture

Moving from cost control to value creation does not mean loosening governance. It means upgrading it.

For CFOs, this requires a subtle but significant shift. Consulting must stop being treated as a necessary inconvenience and start being treated as a strategic asset class. One that deserves visibility, benchmarks, performance tracking, and selective pressure.

That does not mean turning every project into a spreadsheet exercise. It means insisting on clarity where ambiguity has become comfortable. What problem was this project meant to solve? What changed as a result? Would we fund it again, knowing what we know now?

These are not hostile questions. They are the questions finance leaders ask everywhere else.

Until consulting is subjected to the same intellectual honesty as other investments, organizations will continue to confuse spending discipline with value discipline. They will feel in control while quietly paying a premium for uncertainty.

And that, for a CFO, is a remarkably expensive blind spot.

CFOs rarely lack data. What they lack is visibility.

On paper, consulting spend is visible. In practice, it is fractured, diluted, and politically neutralized. Finance systems faithfully record invoices, but they do not explain intent. They capture cost, not context. They tell you that money was spent, not pourquoi, for what outcome, ou alors whether it made any difference at all.

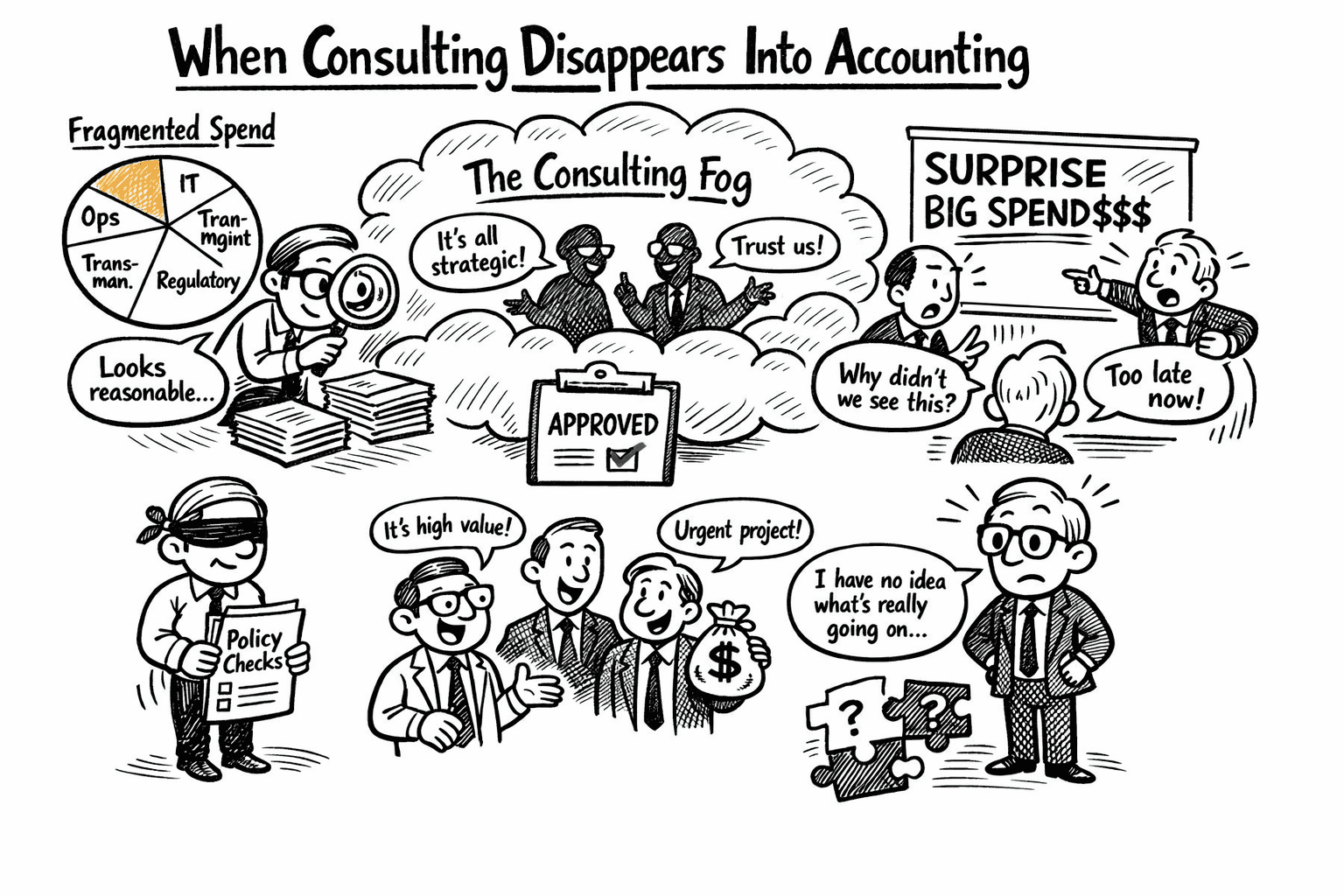

When Consulting Disappears into Accounting

In most organizations, consulting does not exist as a category that finance actively manages. It exists as a label that disappears the moment it hits the general ledger.

Once coded, consulting becomes IT services, operational support, change management, digital transformation, regulatory assistance, or some hybrid that conveniently aligns with whoever requested it. Each label is defensible. Collectively, they erase the category.

The result is predictable. Finance leaders see fragments but never the whole. Spend appears reasonable in isolation, justified locally, and therefore immune to global questioning. No single project looks excessive enough to challenge. No single line item carries enough weight to trigger escalation.

This is how multi-million budgets remain invisible in plain sight.

Visibility That Arrives Too Late to Matter

Every so often, someone asks for a consulting spend analysis. A task force is formed. Data is extracted, reconciled, cleaned, debated, corrected, and finally presented. The numbers are almost always higher than expected. The exercise is considered useful. Lessons are noted.

Then life resumes.

The problem is not that these analyses are wrong. It is that they are episodic. Visibility arrives after decisions have been made, contracts signed, and money spent. It informs retrospectives, not choices.

For finance leaders used to real-time dashboards everywhere else, this delay should feel unacceptable. Yet consulting somehow escapes the expectation of continuous visibility. The category is reviewed when it becomes uncomfortable, not because it is strategically monitored.

You Cannot Govern What You Do Not See Clearly

When finance does not have a consolidated, live view of consulting spend across the organization, it cannot influence prioritization. It cannot challenge duplication. It cannot arbitrate between competing initiatives. It cannot compare impact across projects or suppliers.

Most importantly, it cannot say no with confidence.

This is why consulting governance often defaults to procedural checks. Finance verifies that rules were followed because it lacks the information to judge whether the decision itself made sense. Approval replaces arbitration. Compliance replaces strategy.

The Hidden Cost of Fragmentation

Fragmented consulting spend has another consequence that rarely gets discussed: it weakens finance’s position in strategic conversations.

When finance leaders cannot articulate the full consulting picture, others do it for them. Business leaders define value. Consultants define urgency. Finance reacts.

It is the logical outcome of managing consulting through accounting categories rather than economic logic. The organization ends up with detailed financial accuracy and strategic blindness.

CFOs do not need more reports. They need a way to reconnect consulting spend to decisions, outcomes, and trade-offs while those decisions are still open.

Until that happens, consulting will continue to operate in a comfortable gray zone. Visible enough to be paid. Invisible enough to avoid real scrutiny.

Why This Never Fixes Itself (And Why CFOs Have to Care)

If consulting procurement were naturally self-correcting, it would have corrected itself by now.

It hasn’t. And that is not because organizations lack intelligence, intent, or good people. It is because the current operating model actively prevents learning. Decisions are made locally, spend is fragmented structurally, outcomes are weakly tracked, and risk is managed on paper rather than in practice. Nothing in that system creates pressure to improve.

Left alone, consulting spend does exactly what any loosely governed category does: it grows, spreads, and normalizes itself.

The Myth of “Business Ownership”

A common response from finance is to push consulting responsibility back to the business. After all, business leaders know what they need, sponsor the projects, and work with consultants day to day. In theory, this sounds reasonable. In practice, it is a convenient abdication.

Business owners are incentivized to deliver locally, not to optimize globally. They care about speed, support, and execution within their perimeter. They are rarely rewarded for challenging scopes, benchmarking prices, or questioning whether external support is still justified six months in. Expecting them to behave like portfolio investors is optimistic at best.

Finance would never delegate capital allocation discipline entirely to project sponsors. Consulting should not be different.

Procurement Alone Cannot Carry the Weight

Procurement teams often try to impose structure on consulting spend. Preferred supplier lists, rate cards, sourcing processes, competitive tenders. These tools matter, but they are insufficient on their own.

Buying Consulting is not just about buying cheaper hours. It is about buying better outcomes. Procurement can optimize price and process, but it cannot define value in isolation. Without finance actively shaping the rules of the game, procurement is left enforcing compliance rather than enabling performance.

This is how consulting procurement becomes procedural instead of strategic.

Why CFOs Are the Only Ones Who Can Break the Pattern

The uncomfortable reality is that no function other than finance has both the legitimacy and the perspective to change how consulting is managed.

CFOs sit at the intersection of spend, risk, governance, and performance. They care about visibility because it enables choice. They care about ROI because it signals discipline. They care about compliance because it protects the organization. Most importantly, they have the authority to redefine what “good” looks like.

When CFOs stay passive, consulting remains a tolerated expense. When CFOs engage, it becomes an investment category with expectations.

This is not about micromanaging projects or second-guessing executives. It is about setting standards. What must be visible. What must be justified. What must be measured. And what will no longer be accepted simply because “this is how we’ve always done it.”

The Cost of Doing Nothing Is Predictable

Organizations that do not actively manage consulting as a category do not collapse. They drift.

Spend increases without clear correlation to impact. The same firms reappear across projects with little cumulative learning. Risk accumulates quietly. And finance continues to explain results it did not influence.

CFOs who recognize this pattern have a choice. They can continue to rely on governance designed for control and accept whatever value happens to emerge. Or they can reassert financial leadership over a category that has been allowed to operate on trust, habit, and fragmentation for far too long.

The next section makes that choice concrete, by looking at what actually changes when consulting procurement is treated as a strategic system rather than an administrative process.

What Actually Changes When Consulting Is Managed Like an Investment

This is usually the moment where articles drift into abstractions. “Better alignment.” “Enhanced collaboration.” “Improved decision-making.” Comforting phrases, light on consequences.

Let’s be more precise. When consulting procurement is treated as a strategic system rather than an administrative process, three things change immediately—and uncomfortably—for the better.

First: Consulting Becomes Visible as a Category, Not a Side Effect

The most disruptive shift is also the simplest: consulting stops hiding.

Instead of being scattered across cost centers and mislabeled in accounting structures, consulting reappears as what it actually is—a transversal investment category spanning strategy, IT, operations, transformation, and risk. Not retroactively. Not once a year. Continuously.

It is about creating a single source of truth that connects projects, suppliers, spend, and outcomes. When finance can see all consulting activity in one place, conversations change. Questions become sharper. Trade-offs become explicit.

And suddenly, the organization can no longer pretend that consulting is “under control” without defining what control actually means.

Second: Governance Stops Being Defensive and Starts Being Economic

Traditional consulting governance is designed to protect the organization from procedural failure. Was the supplier approved? Was the budget validated? Were legal steps followed?

Investment-oriented governance asks different questions. Why this project rather than another? Why this firm for this problem? Why now? What would success actually look like—and how will we know if we missed it?

This does not slow things down. On the contrary, it removes ambiguity. When expectations are explicit, fewer projects rely on intuition and sponsorship alone. When benchmarks exist, pricing debates become factual rather than emotional. When past performance is visible, supplier selection stops being anecdotal.

Governance stops being a brake. It becomes a filter.

Third: ROI Stops Being Theoretical

This is where most organizations quietly give up. Measuring ROI on consulting feels difficult, subjective, and politically risky. So they don’t.

Managing consulting as an investment does not require false precision. It requires consistency. Defining expected outcomes upfront. Tracking delivery against those expectations. Comparing similar projects across time, scope, and suppliers. Learning which types of engagements tend to create value—and which reliably disappoint.

Over time, patterns emerge. Not perfect answers, but directional intelligence. Enough to inform future decisions. Enough to stop repeating the same mistakes with confidence.

This is how consulting spend becomes cumulative knowledge rather than recurring amnesia.

Why This Is Exactly Where Consource Fits

Consource does not exist to magically “optimize” consulting spend or make it cheaper by default. It exists to make consulting visible, governable, and comparable in a way finance can actually use.

By centralizing consulting projects, suppliers, and spend in a single platform, Consource gives CFOs something traditional finance systems never provide: a consolidated, operational view of the consulting category while decisions are still being made—not months later.

Consource structures the entire consulting lifecycle, from sourcing and RFPs through project execution and follow-up, with governance embedded directly into workflows. NDAs, approvals, and decision steps are not separate controls layered on afterward; they are part of how consulting is procured and managed from the start.

Over time, this creates something most organizations lack entirely: continuity. Projects are no longer isolated events. Suppliers are no longer evaluated in a vacuum. Finance can see how similar engagements were sourced, what they cost, how they were governed, and how they played out across the organization.

This is not about predicting ROI with artificial precision. It is about creating comparability—across projects, across suppliers, across categories of consulting—so future decisions are informed by experience rather than memory or habit.

Consource is designed to operate either stand-alone or integrated with existing systems via APIs, allowing finance and procurement to regain visibility without disrupting existing processes. And because consulting involves sensitive information by nature, the platform is built with enterprise-grade security and compliance in mind, including SOC 2 Type II certification.

Most importantly, Consource allows finance to reclaim its natural role. Not as a gatekeeper validating invoices, but as a steward of a category that influences strategy, execution, and risk far beyond its accounting footprint.

This Is Not Transformation. It Is Catching Up.

None of this is radical. CFOs already apply this logic to capital allocation, M&A, and major IT investments. Consulting has simply been allowed to lag behind, protected by complexity and politeness.

What platforms like Consource do is remove the excuses. Once visibility exists, indifference becomes a choice. Once benchmarks are available, overpaying becomes deliberate. Once outcomes are tracked, repeating low-impact projects becomes indefensible.

At that point, consulting procurement stops being a blind spot. It becomes a lever.

And CFOs regain something they quietly lost along the way: the ability to say, with evidence rather than hope, that this spend is not just controlled—but worth it.

Conclusion — The Most Expensive Blind Spot Is the One You Accept

For years, consulting has benefited from a peculiar form of immunity. It is expensive enough to matter, complex enough to intimidate, and strategic enough to discourage uncomfortable questions. As long as governance exists and nothing goes visibly wrong, the category is allowed to operate on trust, habit, and good intentions.

That tolerance is no longer neutral. In a context of tighter budgets, higher scrutiny, and rising risk expectations, not knowing where consulting money goes is no longer a harmless blind spot—it’s a leadership failure.

The irony is that CFOs already know how to manage this kind of problem. They do it every day with capital investments, acquisitions, and major transformation programs. Consulting was simply left behind, framed as support rather than as the investment it has always been. The result is a category that feels controlled while quietly escaping the discipline applied everywhere else.

Closing this blind spot does not require turning finance into a consulting police force. It requires restoring financial logic where it has been politely suspended. Visibility that reflects reality, not accounting labels. Governance that evaluates choices, not just compliance. Performance tracking that creates learning rather than justification. And risk management that acknowledges influence is as sensitive as capital.

This is where Consource changes the equation. By giving finance leaders a clear, consolidated, and continuous view of consulting activity, Consource allows CFOs to move from passive approval to active stewardship. Consulting stops being a tolerated cost and becomes a managed portfolio. Decisions regain traceability. Value becomes discussable. Indifference becomes impossible.

The uncomfortable truth is that the blind spot was never technical. It was cultural. And cultures change when leaders decide that “good enough” is no longer acceptable.

If consulting matters to your organization—and it does—then it deserves the same rigor as every other strategic investment.

Réserver une visite guidée gratuite de Consource.io et découvrez comment vos achats de services de conseil peuvent enfin fonctionner comme il se doit.

0 commentaires